The Monk Seal Conspiracy

4. The Secret Police

‘I suppose the rats have been in your house as well.’ The disembodied voice which called out from along the pathway was strained and subdued, yet eerily devoid of emotion. For a moment Rita’s words seemed to hang suspended, shivering in the mute stillness of the night. The metaphor was stunning, playing instinctively on the fear and repulsion which she felt for the large black rodents which had once inhabited her kalivi. Although she had managed to drive them out, she still shuddered to remember how they panicked and squealed when cornered, how, to her dismay, she had once found one burrowing into a kitchen drawer, how they had scurried across the floorboards at night and, once or twice, even over her face as she slept. But the image now conjured up a plague of rats of an entirely different kind, rats in semi-human form from the cities and sewers, with hunched backs and grey, greasy fur, inquisitive pointed faces and tiny prying eyes, squeaking to each other in nervous excitement, candles in their claw-like paws, scrutinizing our letters, groping through our belongings, and turning our homes into rubbish tips.

The implications of the raid were only just beginning to dawn upon me. My mind was bombarding itself with questions, but solutions to the puzzle remained infuriatingly elusive. Who could have been responsible and for what conceivable reason? Were the police themselves mixed up in this? Did the orders originate from Athens or only from Samos, perhaps a local army or intelligence chief acting on his own initiative? I imagined a pugnacious and hot-headed individual in uniform, giving vent to his own frustrations and his obsessive derision for Greece’s nascent democracy. Even though the military Junta had fallen in 1974 with the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, it was common knowledge that many of its most faithful functionaries were still resisting the civilian government’s efforts to purge the security forces. Vestiges of the Junta were clinging tenaciously to their positions of influence, and continued to command the loyalties of wide sectors of the military bureaucracy. Behind the scenes, an intimidating war of nerves was still in play, stunting the government’s reforms. There were even rumours that some disaffected officers were daring and willing the government to go too far too soon in its liberalization, provoking a backlash amongst the Junta’s diehards.

That they were still able to resort to such blatantly illegal acts as the break-ins at our houses not only revealed the extent of their power, but also their contempt for the civilian ministries in Athens. Fleetingly, it crossed my mind that the raid might have been specifically designed to embarrass the ministries that we were co-operating with in Athens, but I quickly discounted this as my own paranoia. It seemed much more likely that this was the result of some bureaucratic blunder, perhaps even a case of mistaken identity. But what would be their next move? What would be ours? This was our immediate dilemma.

Both of us were now wide awake and, after the initial shock of it all, anger and indignation began to seethe within us. If we ignored the raid, our silence could be misconstrued as an implicit admission of some still hidden guilt. If on the other hand we raised a hue and cry over the affair, we might jeopardize our fledgling project to protect the seals of the islands. If we went to the press with the story, it might endanger our co-operation with the ministries in Athens who were supporting our endeavours. Loyalties and patriotism would immediately be called into question, placing them in an awkward and embarrassing predicament. Realizing the wary pragmatism and expedience of government policies in the capital, they would undoubtedly be obliged to side with military intelligence in the eastern Aegean, which, because of fears of Turkish hostility, was considered to be the most undiminished outpost of the Junta’s influence. We were, after all, only small-fry ecologists working to save an obscure species from extinction, and without government support our efforts would quickly founder. Compared to military priorities and the seething backstage power games in Greek politics, we were not only vulnerable but entirely irrelevant. At least, this is what we deduced at that time.

Little did we realize that the monk seal project would actually become trapped in an almost frantic tug of war, pushed and pulled between the civilian and military sectors of the government. Outlandishly, the monk seal affair would come to symbolize this antagonism, a convenient battleground for a test of wills, and a microcosm of the country’s hidden yet tumultuous political undercurrents. It would not be inspired by any feelings of compassion for the species or even genuine concerns of national security. At stake was an inexorable competition for political influence, with the monk seal project caught in the crossfire. For both the civilian and military sectors of the government, it was to become a matter of blinding principle and stubborn pride.

Still buoyed up by the return to democracy after the brutal seven-year reign of the colonels, the ministries in Athens would find it inconceivable that the military diehards in the eastern Aegean could meddle in such apparently benign affairs of state. On the other side, the chiefs of military intelligence would view the seal project as an almost decadent self-indulgence, and ostensibly at least, as evidence of the government’s intolerable laxity over national security. But concealed behind all the pious sophisms would be nothing more than a sordid squabble over power, one side still intoxicated by the heyday of the colonels and clinging limpet-like to a bankrupt era; the other side building up the foundations of its stability and its grip over governing the country, investing its hopes in dream-corrupting expedience, quite prepared to sacrifice the monk seal should its principles suddenly become a liability.

If the raid had been a deliberate attempt to intimidate us, then there could be little doubt that the security forces would scrutinize our reactions. Perhaps they were hoping that we would scuttle out of the eastern Aegean immediately, or, if they genuinely suspected us of being spies, that we would be bound by a professional code of silence, putting our espionage activities into cold storage while waiting nervously for their next move. Looking back on it now, it was perhaps inevitable that the conspiring minds of YPEA would interpret almost any reaction on our part as a tacit admission of guilt, since even the most spurious allegations are usually dependent upon the deliberate perversion of quite innocent events. In this sense, it was quite possible they were hoping that the raid on our houses alone would push us into some fatal over-reaction. But as we saw it at the time, there was no other option for us than to appear entirely natural, innocent and even naive. We would have to report the break-ins to the police.

By about nine o’clock that evening we were driving along the drab sea-front of Ayios Konstantinos, with its gigantic boulders piled up along the shore as breakwaters against the winter storms, its dilapidated houses, and on these long wintry nights, its few caféneons stuffy with condensation, reeking acridly of Greek tobacco, men playing backgammon or cards under the harsh fluorescent lights. We rolled to a halt outside the village police station but there was no sign of life. Its doors were padlocked and its windows, which look out across the sea, were tightly shuttered. In all likelihood, however, at least one of Ayios’s three policemen would be spending his evening sitting around in the caféneon of Costas and his dwarfish and eccentric wife Elpeda. For the men, at least, this is the hub of village life. On three days of the week it also serves as the village post office, when at some time in the morning the postman arrives from Vathi and blows a trumpet up and down the sea-front to summon the villagers to collect their letters, pay their bills and buy stamps. On Sundays it is transformed into a barber’s shop. The barber too comes in from Vathi, carrying the tools of his trade in a battered leather case, while a grumbling Elpeda drags out a peeling mirror which she tilts against the wall and a rickety green leather chair, probably a relic of the village’s own barber’s shop which died long ago with the barber himself. The caféneon is also the main telephone exchange, an antique piece of equipment which divides the village’s only line into different extensions – the local hotel, the mayor, the police.

Every few weeks, the caféneon also becomes a picture palace, still an exciting attraction for such a sleepy village. The small-time entrepreneurs of these itinerant cinemas tour the island’s more remote villages in rusty vans, equipped with decrepit projectors, scratchy Hollywood films and a white bed-sheet to act as a screen. In summer they set up shop in the platea or village square; in winter, the villagers cram themselves into the caféneon, chattering excitedly, and with great difficulty hush each other into silence as the projector begins to whirr and flicker. On this particular night, a Humphrey Bogart thriller was captivating its audience and we had to crawl under the sheet screen which covered the doorway. Sure enough, we found one of the village policemen tucked away in a corner, evidently spellbound by the film. Because of his ample paunch, he was known locally as Hondro, ‘the fat one’, and his resentment of this nickname, like some kind of psychological indigestion, often caused him to be brusque and churlish. It was in this manner that he greeted our news of the burglaries, and he seemed to regard it as a supreme impertinence that we had barged in just as the plot of the film was reaching its most suspenseful climax. Bogart’s private eye was bounding over the bed-sheet screen, gun in hand, speaking cool fluent Greek to some treacherous dame in a sequinned dress. Compared to this, two break-ins in this normally crimeless village must have seemed profoundly trivial to him. There again, his surly attitude may have had other reasons. It was perhaps quite feasible that he had known about the raid for days. ‘The police station is closed,’ he told us irritably. As he returned his gaze to the screen he added with finality, ‘Come back tomorrow or go to Vathi.’

Incredulous and even more suspicious, we decided to drive back along the coast road and report the incident at Samos police headquarters. We wandered up to the desk acting like bewildered tourists and deliberately pretended not to know any Greek. By this time it was about ten o’clock and only a night duty officer of very minor rank was present. He spoke only rudimentary English, but when we finally made it clear that we had houses in Ayios Konstantinos, a glint of realization seemed to come into his eyes. He picked up the telephone and dialled a number which we were both able to memorize. We deduced from the tone of his voice, which became markedly obsequious, that he was speaking to one of his superiors. Obviously not realizing that Rita spoke fluent Greek, he announced, ‘The two foreigners are here from Konstantinos where we made the research.’ It was the first blunder of its kind which was to enrage the chief of police, Kyrios Theophilos Drumpis. The voice on the other end of the line became discernible for the first time, having risen several decibels. To judge from the cringing reaction of the duty officer, gulping nervously, his face reddening, the voice had become distinctly hostile. ‘No sir,’ he endeavoured to reassure his superior as terrible doubts crept into his own mind, casting us a furtive and worried glance, ‘they certainly don’t understand a word I’m saying.’ When he replaced the receiver a few moments later he turned to us, his face as pale as a ghost, and announced in broken English that children were probably responsible for ransacking the houses. ‘Ti na kanoumay?’ he asked us with a shrug of hopeless fatalism. It is a ritual and often exasperating refrain among the Greeks, meaning ‘what can we do?’

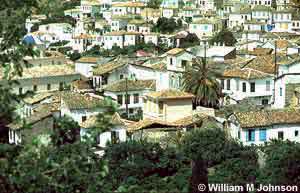

The following morning the sky had lightened and the sea was oyster-grey as we made our way once again to Vathi and police headquarters. Fanned about the hillsides, the old town with its domed churches, its narrow stone streets and its tall, top-heavy houses looked down over the wide bay and bustling harbour.

I was soon to wonder whether Theophilos Drumpis might be prone to morbid superstitions. In the early hours of the morning, a school bus had plummeted off the tortuous mountain road near the village of Vourliotes, a number of children had been killed and injured, and the chief of police had not only suffered a tongue-lashing from his own superiors, he was also under virtual siege by a hostile national press. The towns and villages had become hives of rumour and gossip: the bus driver was tired and drunk after an all-night feste, the bus had bald tyres and faulty brakes, the narrow winding road is actually prohibited to such large vehicles but the police have always turned a blind eye to them…

Despite all the commotion at police headquarters, Kyrios Drumpis managed to find a few spare moments for us by mid-morning when he at last allowed the flustered and quivering bus company chief to leave his office. We were shown in right away, accompanied, to our great surprise, by the head postmaster. Mr Drumpis had summoned him to act as interpreter. Both had yet to learn that this was unnecessary, and it would eventually be a rude awakening. Kyrios Drumpis shook hands with us, though half-heartedly. His mind was obviously absorbed with more pressing matters and perhaps this explained his erratic mood swings during our meeting. At times he could barely disguise his resentment at our intrusion, but a moment later he would appear most sympathetic and concerned at the plight of these bewildered foreign tourists. Only the hard glint in his eyes betrayed him, and we suspected that his brief lapses into politeness were merely a ruse to deceive the postmaster. It occurred to me that this might have been the pugnacious individual in uniform whom I had envisaged giving orders for the raid. He scrutinized us from under his bushy eyebrows, a thick-set man in a creased uniform, as though he had spent the night sleeping in it. His hair was bristled, shaved around the ears and tufted almost comically across the crown of his head. How ironic it was that St Irene of Peace, patron saint and protector of the Greek police force, was framed on the wall opposite me, looking down over Mr Drumpis’s slab-like head, witnessing yet another peculiar incident in the annals of police history on Samos.

With the postmaster translating for us, we informed Mr Drumpis that we were working in association with the National Council for Physical Planning and Environment (NCPPE), a section of the Ministry of Co-ordination, and that our proposals for the protection of the monk seal in the eastern Aegean were being submitted, with their stamp of approval, to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. We hardly needed to say anything else since by this time Mr Drumpis was shuffling papers on his desk, smiling broadly at us and almost over-exerting himself with expressions of affability and concern. But there was still a certain nervousness discernible, not least of all in the way in which he continued to tidy up papers on his desk without any apparent purpose or success. When I informed him that the break-ins would have to be reported to the Ministry of Co-ordination, the beaming smile suddenly froze on his lips. He immediately rose from his seat and, dispensing with the postmaster’s help, announced in halting English with the benevolence of a kind father-figure, ‘Really not necessary. Police here for your protection. Anything you need, just come ask. Only children… Ti na kanoumay?’

‘But surely children don’t steal films out of cameras?’ I asked. I was annoyed that the chief of police could have offered such a feeble and unimaginative explanation, and I wanted him to know of our suspicions without explicitly voicing them. Coupled with support from Athens, I hoped it might act as an insurance against any further harassment by the police. For the sake of the monk seal alone a vendetta had to be avoided at all costs. ‘The police are sure it was children,’ Drumpis replied, the irritation once again creeping into his voice. ‘Will the police be mounting an investigation?’ I persisted. ‘There are fingerprints all over the place.’ ‘The police will make enquiries,’ Drumpis replied with finality. ‘Research at your homes will not be necessary.’

|

|

Vathi, Samos.

|

Despite his conciliatory attitude I decided to report the incident to the NCPPE, since we were already working closely with the agency on the protection of the monk seal. Later that same day, the permanent secretary of the Council, Marinos Yeroulanos, telephoned Mr Drumpis and perhaps rather too bluntly asked him to cease his harassment, and to co-operate with our endeavours to save the monk seal. We were soon to wonder whether this had been a mistake, only serving to antagonize and provoke the chief of police into a vendetta against us. But on the other hand we found it inconceivable that Drumpis alone could have given the order for the raid. Furthermore, the clandestine style of the operation did not seem to bear the classical hallmarks of the uniformed police, unless perhaps it had been some kind of atavistic reprise from the days of the Junta, or perhaps the personal obsession of some officer whose nostalgia for the colonels had suddenly become uncontrollable. It was also true that Drumpis himself was prone to flights of fancy. A year earlier, at the height of the summer tourist season, he had spearheaded a ‘task force’ raid against nudism on a popular sandy beach just outside the village of Kokkari. The naked tourists had been taken by complete surprise as three boats manned by the police came in a sweeping arc around the bay to make a daring commando-style raid on the shore, while an army helicopter hovered overhead taking photographs, and a convoy of vehicles, led by the jeep of Kyrios Drumpis, arrived to block off exits by road and pathway. Everyone on the beach who had been ‘indecently’ exposed was arrested and promptly escorted to the Vathi law courts in a black maria. There, the already primed judges, with a flourish of judicial hammers and a flood of harsh and moralistic diatribe, pronounced the helpless and bewildered collection of tourists, and even their children and infants, guilty of ‘corrupting the morals of the nation’.

Yet these explanations, although plausible, seemed unconvincing, and it was at this time that we first began to suspect the involvement of YPEA, the Intelligence Service for National Defence. This shadowy counter-espionage service shares its home with the Greek police force in the Ministry of Public Order, which seemed to explain the vague yet undeniable role of Drumpis in the affair. Later that afternoon we visited the postmaster, who was still aflame with curiosity. The mystery and intrigue of the affair was to cement a lasting friendship between us, and over the following months we were to spend many hours in his private office, calling on him for advice but getting waylaid with numerous cups of muddy Greek coffee and profound discussions on the philosophy of life. He was bored to tears by the drudgery of office work and in the habit of seeking out any diversion he could think of to pass the time. Tall and suave, his sleek grey hair swept back over his thinning temples, the postmaster also had something of a reputation as a ladies’ men and inevitably, with great charm and elegance, would accost any pretty young female tourist he came across in the foyer of the post office, as they queued up to buy stamps for their picture postcards.

He could also talk almost interminably about his crumbling marriage, his ungrateful son, and his romantic nostalgia for when, in the middle of the 19th century, Samos had cast off the yoke of Turkish occupation to become an independent protectorate of the great powers. The island had had its own elected parliament, Vathi had become a thriving maritime centre, and the flags of the greatest nations on Earth had flown majestically from the facades of the quayside buildings that housed their consulates. Imparted to the island had been an internationalism, a cultural splendour, music, the arts, theatres and festivals, horse-drawn carriages in the streets, the most elegant ladies and gentlemen… ‘How low we have sunk since then!’ he would declare, returning from the trance with a sorrowful sigh and a disdainful grimace for the island’s unbearable provincialism.

He spoke guardedly and in hushed tones about the Junta years, but did not seem even slightly cowed by the mysterious raids on our houses. Nor was he unduly surprised, although the affair was perhaps intriguing enough to offer some welcome relief from his life’s provincial boredoms. He endeavoured to trace the telephone number which we had seen the duty officer dial the previous evening, and this turned out to be one of Samos’s few restricted numbers.

Several days later, yet another bizarre incident occurred. After meeting with the postmaster again, and persuading him to have several thousand booklets on the monk seal distributed through the post office, Rita was walking through the ornamental gardens in front of the building. It was already dark. Suddenly, a hand gripped her from behind, clasping itself over her mouth. It belonged to the parcels officer who, it appeared, harboured some grudge or jealousy against the postmaster. ‘Ritiki-mu’, he whispered hoarsely, using the intimate Greek diminutive of her name, ‘what is going on between you and the postmaster?’

The effects of these strange days gradually subsided, leaving us free to concentrate on our work in the days of incredible winter blueness when the wind comes in from the north-west. We were only troubled by the rumours in Ayios Konstantinos. They seemed to suggest that we suspected village people of breaking into our houses. The thought had never crossed our minds and it was an obvious slur against the community. It marked the beginnings of the YPEA defamation campaign.

|